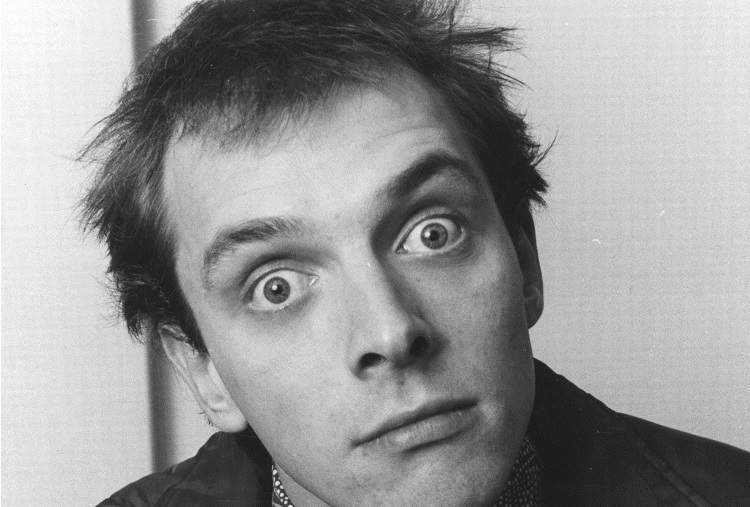

Rik Mayall c.1981, in “A Kick up the Eighties”. Photo: BBC

In what must be something of a record, my tears started at around fifty seconds in to Lord of Misrule, BBC2’s Rik Mayall tribute (which airs on Saturday 20 December, sandwiched between episodes of Blackadder and The Young Ones). It was Ben Elton that set me off; it’s been a long time since he produced any kind of emotion in me at all, but when he called Rik a “golden youth” he sounded so tender and wounded I was gone.

As Elton spoke the programme cut to early footage of this golden youth looking like no golden youth you’d imagine. In a clinging grey polyester polo neck, sloop-shouldered and concave-skinny, Rik shrugged and turned his wide-mouth smile to the audience, all teeth and cheek. Elton was right. You can see Rik’s whole performing life in that look, the beautiful man of a generation, the “force of nature” as Tim McInnerny later describes him.

At the start, Mayall offers his own ideas of what a tribute to him should look like. “Surely it should just be Rik, talking about himself, on his own, forever,” he said. Lord of Misrule instead takes a chronological approach, narrated with booming hyperbole by Simon Callow. “On the day he was born, the gods cried ‘Let there be Light Entertainment’,” he declares, though LE is not something we usually associate with rude wit and creative anarchy. Packed with archive footage and heartfelt reminiscing, the programme also features director Michael Cumming’s previously-unseen 2010 interview with Rik. “I like millions and millions of people looking at ME,” Rik says in it. “Just looking at ME.” His face fills the screen, he’s right there, and we are looking at him. It makes him feel very, very present, underlining the great sense of loss that pervades the programme.

As Alexei Sayle says, Rik “could make you laugh, saying nothing”, a skill he learned at school. Forbidden from joining in the hymn-singing, he distracted his classmates and discovered that comedy had valuable currency. “I like this,” he said with alacrity. “I like these laughs.” And they seemed to come easily. In an early TV interview with him and Ben Elton, while Elton earnestly explains new forms of comedy, Mayall quietly pulls focus by folding his ear into itself. Elton realises what’s going on and gives in. Rik looks to camera and gestures “Who, ME?” He knew.

It’s about now, when Dangerous Coyote are introduced, that we expect an appearance from Ade Edmondson. But it doesn’t come. We get Sayle, Lenny Henry, Pauline Melville, Ruby Wax, Greg Davies, Lise Mayer – a whole host of Mayall’s collaborators, talking with love and generosity. But no Edmondson. Maybe it’ll come later, we think.

The first half of the tribute centres round The Young Ones, and it’s astonishing to be reminded that it was a mere twelve episodes, and that Rik was 24 when he did it. Twelve eps! Twenty four! Rik came out of it “the most successful and most loved comic in Britain at the time,” says Elton, and surely no one would disagree. Smart, funny, full of “love, anarchy and wonderful violence”, this was comedy for the kids. “You felt you were in on the joke,” says Greg Davies. “Laughing with him and at him, it was so exciting.” This key to his success is echoed through the programme – the feeling that he belonged to us, was one of us, not a Remote Star twinkling somewhere above us. Sayle has a prosaic explanation. “If you went to Oxbridge, you had a particular sense of entitlement, and [they] didn’t have that. They weren’t polluted with that way of doing things.” It was ours, for us, he was ours. He knew that, and revelled in it. Where other performers might gain deferential respect, “there was something that came through the persona that made a direct connection with people, which was very unusual” says producer John Lloyd. And of course the upshot of that direct connection is the outpouring of personal grief on his death.

Another part of why we loved him may be that he loved himself. “He enjoyed being Rik Mayall enormously,” says Ben Elton “and hilariously”. This great big show-off who loved performing appeared to have no self-doubt and equally, only fake arrogance. He wanted it, and when he got it, he was very happy. It’s so uncomplicated. And his confidence and pleasure rubbed off on us – all of which sounds a bit sleazy and surely would have earned a raised Mayall eyebrow.

After Comic Strip and Alan B’Stard, the programme goes on to Bottom, and here, you think, here surely Ade Edmondson will be on. Still no show. It’s hard to judge whether his absence leaves this tribute incomplete, as there’s no placebo tribute to judge it against. It’s certainly a shame he wasn’t able to contribute. But we can only work with what we have and what we know, and we know this: that there is no one better than the BBC to make such a warm and loving tribute to a comedy hero, and that Ade would have been approached to appear. The rest is detraction and speculation.

What this tribute is full of is masses of his wild and wonderful, crude and poetic comedy. Inevitably, the mood changes in the last five minutes. On 9 June, 2014, Rik Mayall is dead. He almost died once before, but rose again. “Lord knows I’m a modest man,” he says, “but I beat Jesus by two days”. His death made the front page of every newspaper, which was “quite right too” says Greg Davies, given how special he was. In the final minutes of the programme we hear the conclusion of Rik’s speech as he accepted an honorary doctorate from the University of Exeter. (The whole speech is up on Youtube, I urge you to look at it.) In it, Rik tells the audience the secret of life. And love is it. Love is the secret. It’s what he gave us, and what we felt in return. Talking about Comic Strip, Mayall said: “I wonder if comedy was slightly more proud in those days. You could make a larger, prouder twat of yourself.” He may have been a large, proud twat, but he was our large proud twat. And we loved him for it.